Managing paediatric deformity with TSF◇

Patrick Foster, FRCS; Leeds Teaching Hospitals, UK

The views and opinions expressed in this section are those of the surgeon.

Principles

Deformity correction in children is “orthopaedics” in its purest form when considering the origin of the word from the Greek meaning “straight child.” TSF is an extremely versatile and powerful tool for this type of work and if used correctly after appropriate training is safe and tolerated very well by children. Circular frames (including TSF) are also extremely safe and effective for treating complex tibial fractures in children but this chapter will focus on deformity correction.

Pre-operative planning and preparation is paramount, even more so when compared to adults. As well as standard deformity analysis and planning (don’t forget rotation), the added dimension of timing is crucial, as the bones are still growing – the surgeon must be aware of the natural history of the condition he or she is treating. Sometimes it is easier to wait until the child has stopped growing and treat the residual and permanent deformity rather than a “moving target.” However often it is not required or appropriate to wait that long, and at the other age spectrum, although TSFs can be applied on very young children (when absolutely necessary), it is generally easier for the child and family to understand and cope after reaching the age of six. Other timing issues may be important such as school examinations in older children.

As well as bone length discrepancy and deformity, the surgeon must take into account joint stability and soft tissue tension before taking on a lengthening with TSF, particularly with Congenital Femoral Deficiency and Fibula Hemimelia. Additional surgical procedures may be required before the lengthening, either separately or at the same sitting as TSF application. This may be a simple procedure such as gastrocnemius or ilio-tibial band release, or more major such as pelvic osteotomy (such as Dega) to improve hip coverage. It is much easier to prevent hip and knee dislocation or contracture rather than attempting to salvage the situation during or after lengthening. The frame construct can protect against joint subluxation and contracture by appropriate spanning, such as across the knee into tibia when lengthening the femur, potentially with hinge, and across the ankle into the heel and foot when lengthening the tibia. Post-operative physiotherapy is vital to further protect the joint stability and movement, as well as to promote general mobility, and should be put in place in advance.

In terms of TSF construct and planning, chronic mode is ideal for treating childhood deformity, and gives the child and family a clear picture of what the TSF is going to achieve when the Rings are adjusted from crooked to parallel. The frame should be made stable enough to allow full weight bearing from the outset, and stable enough to be discharged from hospital within a few days and attend school within a week. This means there should be enough Rings on the tibia to make it stable, and enough fixation elements on each Ring to make it stable, just like a frame on an adult. It is a mistake to think that all TSFs should only have two Rings, and a mistake to think that a child’s frame only needs a minimal amount of fixation to the bone.

In terms of wire and pin placement, great care must be made to avoid the growth plates, in particular the tibial tuberosity which is vulnerable to a stray pin – a bone tether in that area soon leads to apex posterior angulation (recurvatum) and shortening. Some surgeons prefer smaller diameter wires (1.5mm) and less tension (90-110kgs) for children than in adults, but in my practice this is reserved only for extremely small bones such as children’s metatarsals and club hand frames for example. If using half pins the 4.5mm pin should be considered instead of 6mm for bones less than 2cm diameter, or an all-wire construct.

For lengthening rate and rhythm the distractions can start slightly earlier than in adults (days six to eight) and at a faster rate (0.8-1mm). In my experience premature consolidation of the regenerate only occurs when the child and family fall several days behind with the planned TSF program. If at all possible the child should be directly involved in the TSF corrections, and other procedures such as pinsite care. I find that children especially appreciate the use of the myTSF app to run the corrections. Once the chronic mode plan is completed I prefer to swap the TSF to straight rods in the outpatient clinic to avoid the temptation for a child to add in some extra turns as well as other benefits such as better visibility on X-ray views and decreased weight. As expected, quality of childhood regenerate is generally better than in adults, hence shorter frame times, but only if a stable frame with enough Rings and fixation elements was applied at the outset. Distal tibia osteotomy and lengthening is just as successful as proximal in children and should be considered if it suits the individual case.

Children often cope extremely well with a stable frame and so are not in a massive rush to have it removed, rather than risk a premature removal and treatment failure which is dispiriting to say the least, particularly in children. Waiting until the regenerate is fully strong also means that upon frame removal, precautions such as casting and activity modification are not required which is beneficial for the child and family all round.

Case example

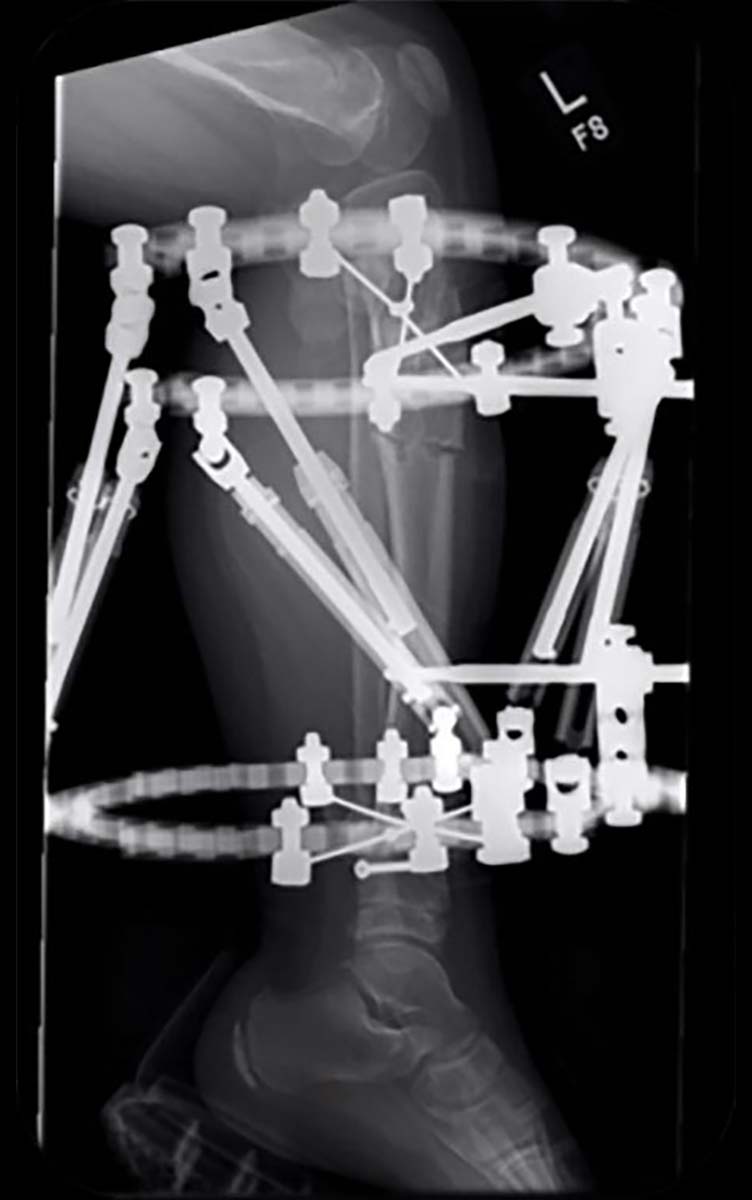

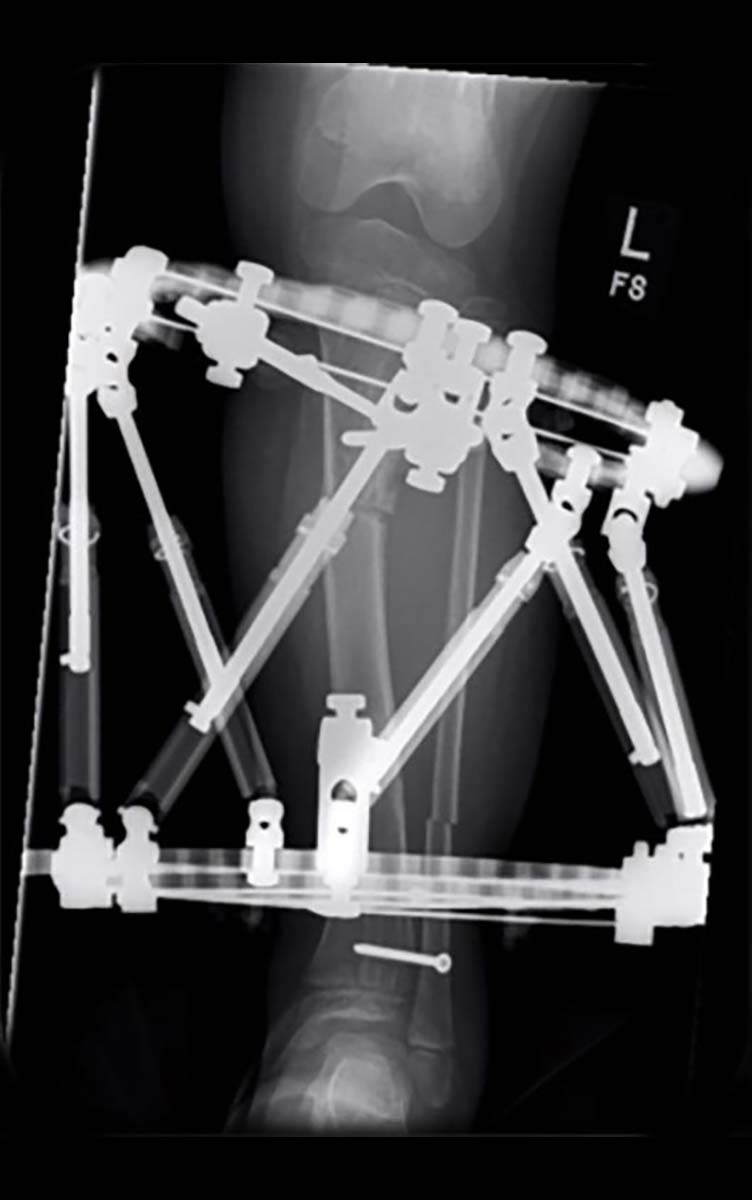

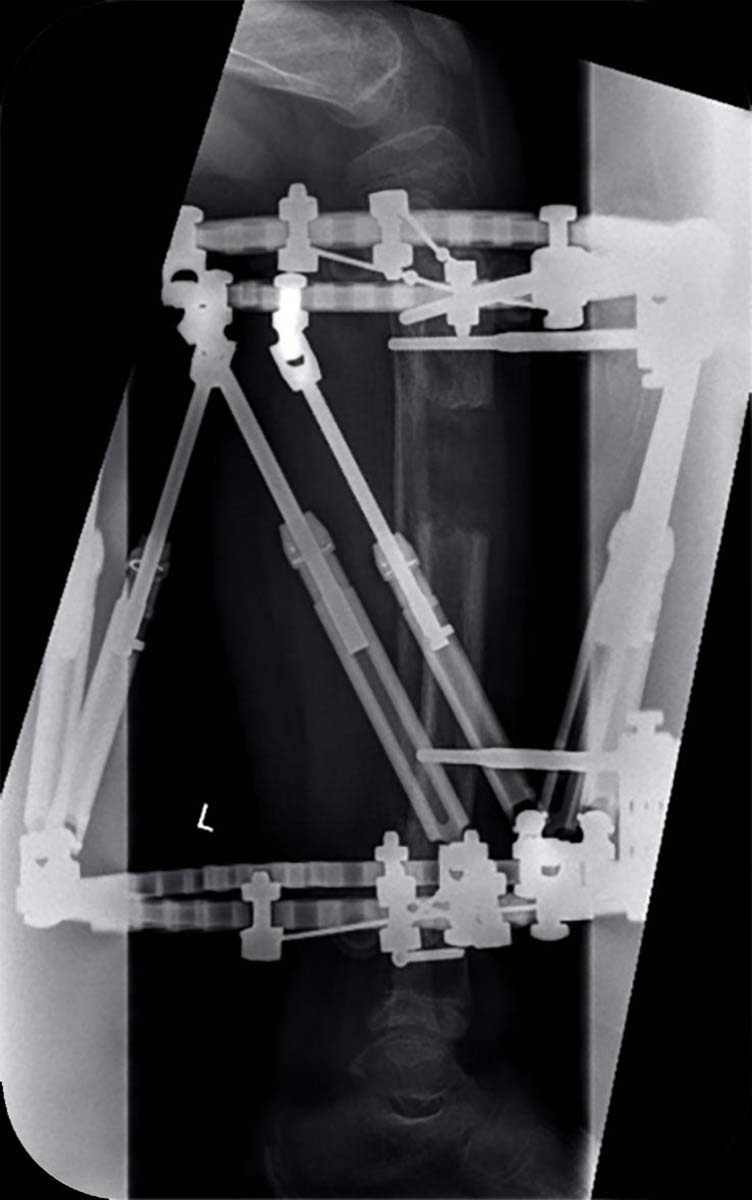

A girl aged six with Ollier disease (multiple enchondromatosis). Following deformity analysis the plan was to lengthen the tibia 4cm with a 15 degree correction valgus to varus in the proximal tibia, and a chronic mode TSF◇ program was made with neutral Strut length of 170mm, so with standard Medium Struts no Strut changes were required. There was no rotational or sagittal plane deformity clinically. With the short length of bone, two Rings were required instead of three on this rare occasion (Figures 1 and 2).

In her case she had a very flexible ankle with over 20 degrees of preoperative dorsiflexion so neither gastrocnemius release nor spanning the ankle was required. After prebuilding the chronic mode construct while the patient was in the anaesthetic room, the fibula osteotomy was performed, and the distal fibula was stabilised to the tibia with a 3.5mm screw (Figures 3 and 4). Some surgeons also fix the proximal fibula to the frame or tibia but in my experience some distal migration of the proximal fibula is of no clinical consequence, and fixation in that area is often irritating to the child.

Figures 5 and 6 demonstrate that great care was taken to avoid the growth plates including tibial tuberosity.

Figures 7 and 8 show the stable construct which matches the deformity.

- Proximal 2/3 155mm Ring with two 1.8mm Olive Wires tensioned to 110-130kgs, and two 4.5mm HA pins.

- Distal Ring 155mm full Ring with two 1.8mm Olive Wires, one plain wire and one x 4.5mm HA pin.

- Proximal tibia corticotomy created with three x 3.8mm drill passes and osteotome through a 1cm incision.

With chronic mode since the TSF◇ program is already done it does not matter if the post-operative X-ray is neither calibrated nor centered exactly on the reference Ring.

Post-operative treatment

Physical therapy can begin on post-operative day one, including weight bearing. Ollier’s is known to lead to swift regenerate formation so turns are started on day six with a rate of 1mm per day. As well as interim clinic appointments the position at the end of the program was checked with X-rays. Upon completion of the correction, Struts can be replaced with Threaded Rods.

After four months the frame was removed under a short general anaesthetic and no cast or splintage was required. Figures 9 and 10 show the clinical and radiological result. With her condition she is likely to develop more of a leg length discrepancy by skeletal maturity so will need at least annual follow-up and probably left femoral lengthening or right-sided epiphyseodesis at the appropriate time.